My Recent Haircut Experience

The mental journey of an Economics major who was unsettled by how expensive his haircut was.

Part of growing up, I’ve learned, is becoming more close-minded.

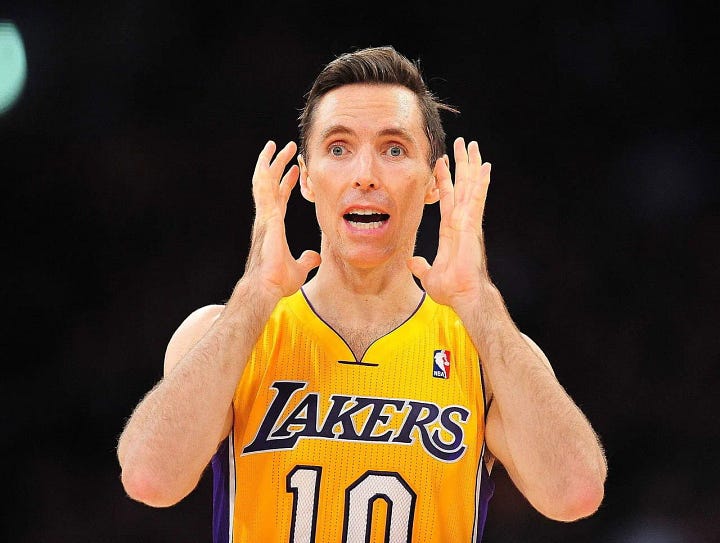

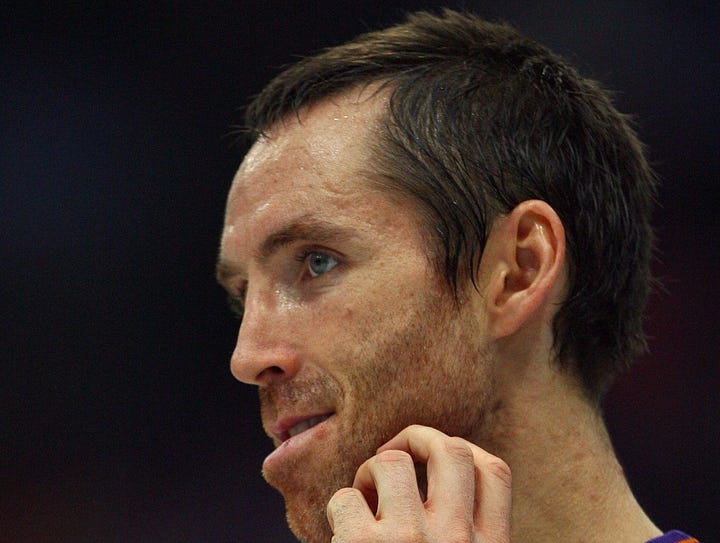

As an 8-year-old I would go to get my haircut thinking about the lollipop I would receive at the end and how closely my hair would resemble Hall of Fame Point Guard Steve Nash’s hair after he signed with the Los Angeles Lakers before the 2012-13 NBA season. When I went to get a haircut last week, I left with thoughts about microeconomics – no lollipop (and hair resembling Steve Nash at the beginning of the 2006-07 NBA season).

The curse of economics is that it provides the language for explaining or describing almost any social phenomenon. Spending time deliberating about the implications of my recent haircut costing $16 despite only taking five minutes is my version of fun. But there are a lot of people who would call instinctually applying economic analysis to everything an unproductive activity.

I think using productivity as a criterion for evaluating things is an unproductive activity. An end that is fun and harmless to others usually is enough to justify the means, whether it is productive or unproductive.1

Prices Tell Stories

Economics is often degraded as a “dismal” science. Others disagree, claiming that economics cannot be called a science. So naturally, it may seem strange to associate economics with fun. But applying economic analysis to prices can reveal a story. A fun story.

Even before I was ever exposed to the dark art of economics, I had always approached getting my haircut as an investment. Haircuts are typically thought of as a consumption good, given that it immediately returns the aesthetic benefits desired and does not store any value or generate income over time. But back when I was eight years old, I subconsciously identified certain inefficiencies in the market for haircuts that I could exploit to generate tremendous cost savings over my lifetime.

Because of the mysterious nature of men’s haircut pricing, the prices of two very different haircuts at the same barbershop can be exactly the same. Prices are not contingent on factors such as the duration of the haircut or the total hair length trimmed. Consequently, someone’s five-minute minimal hair trim could cost the same as another person’s 45-minute maximal hair transformation. This fundamental price equivalence has several implications for both the person receiving the haircut and the barber giving the haircut.

The main beneficiaries of the price equivalence are people that are indifferent towards a greater variance of hair length, who can convert very short haircuts on a less frequent basis into cost savings. People who can only tolerate very little variance in hair length, on the other hand, have to get haircuts more frequently, spending way more money.

A lot of economic analysis is using systematic, sometimes complex, ways of thinking to obtain conclusions that are generally common knowledge. It doesn’t take a genius to intuit that people who care more about their hair appearance will spend more on haircuts.

Receiving short haircuts on a less frequent basis, however, comes with the additional risk of a poorer quality haircut. The more hair that has to be cut off, the greater the chance that the barber messes up at some point. But risk is also embedded within the incentives the barber faces as well.

Barbers likely earn wages based on some combination of commission and hourly wages. In a commission-based model, the least optimal customer for a barber earning commission is someone whose haircut will take a long time, as the barber is incentivized to complete as many haircuts as they can each day. More precision and care might then be applied to the more frequent customer whose haircuts take less time, at the expense of the less frequent customer whose haircuts take more time. Because the more frequent customer probably cares more about their hair, the barbers are further incentivized to apply more precision and care, given that the precious repeat business from this customer must especially be earned.

So the less frequent haircut schedule that I have been following for years is not some kind of arbitrage strategy. Like all investments, it can be characterized as a tradeoff between risk exposure and returns. The less frequent haircut schedule strategy is exposed to what we can call “quality risk.” The risk, of course, being a messed-up haircut.

The Haircut Risk Premium

By choosing a less frequent haircut schedule, I am accepting that the variance of my hair’s length will be greater and that I will be exposed to some idiosyncratic “quality risk.” My expected compensation for accepting these two conditions, or the premium I receive for taking on both risks, is equivalent to the cost savings generated relative to a more frequent haircut schedule.

By choosing a more frequent haircut schedule, I am willing to pay more money to minimize the variance in my hair’s length and my exposure to this idiosyncratic “quality risk.” The money I spend on these haircuts relative to a less frequent schedule is like a premium I’m paying to preserve my hair.

Risk premiums can only be measured relatively. If I forgo two out of a standard twelve haircuts in one year, which each cost $16, and adjust the time between the remaining haircuts to be equal, then my “haircut risk premium” is $32. This means I am willing to exchange greater variance in hair length and a higher probability of a bad haircut than what I would experience within a monthly haircut schedule, for an additional $32 of disposable income at the end of the year.

Whether a certain haircut risk premium is worth it, is a subjective decision every male repeatedly makes over the course of his lifetime. If the barber empirically does not mess up your hair very often and you’re indifferent towards a higher variance in hair length then maybe it’s worth it. Eight-year-old me was willing to take the risk of a messed-up haircut with a higher variance in hair length in exchange for the cost savings generated by getting shorter, but more infrequent haircuts.

Quantifying how damaging a bad haircut can be to a person is a much more difficult task than measuring the haircut risk premium. Luckily economics has made up this thing called utility. There probably exists some point of damage (disutility), where even eight-year-old me would go back to the barbershop to get his haircut fixed regardless of the long-term schedule he predetermined. The trouble, of course, is that if your hair is too short for your liking as the less frequent haircut schedule would suggest, there might not be much hair to fix.

End Big Haircut

With my last haircut, I chose to forego the risk premium that I typically opt into so I could make some minor tweaks to the look of my hair. The growth of my hair over the past few months followed a uniform distribution along the top, sides, and back of my head, as opposed to the heavier distribution on the top that most males typically sport. As a result, I had reached a point of disutility at which I was willing to make an additional trip to the barbershop.

I walked into the barbershop for my scheduled appointment, thinking my uniformly distributed hair grown from scratch would resemble a smooth, blank canvas that my barber would transform into a work of art. But I instead walked out merely five minutes later with $16 less in my bank account feeling very irrational. The haircut itself was decent, but the experience through an economic lens not only cemented my commitment to a less frequent, short haircut schedule but it also brought to my attention the inefficiencies that occupational licensing creates in the market for haircuts.

At first, I considered whether haircut pricing should be more dependent on the duration of the haircut. I honestly was expecting to receive some rebate from the barber for being his fastest haircut of the day. However, neither the barber nor the price he charged acknowledged the unprecedented speed of the whole operation.

But while a pricing model dependent on haircut duration would have benefitted my situation, it would also financially disadvantage people with hair types that require more precision and care, which they cannot control. And given that the US is the country with the most hair type diversity in the entire world, imposing such a pricing model would be less fair than the status quo. A status quo in which the quality risk defined above already disproportionately impacts some hair types more than others.

Then I considered how haircut services could be cheaper, which would immediately benefit everyone regardless of hair type, relative to the status quo. The most simple, intuitive solution would be to increase the supply of barbers, which is currently restrained by occupational licensing regulations.

When I got home later that day, I learned that cutting someone’s hair in exchange for money is illegal without a license obtained by either training, which costs roughly $10,000, or cosmetology school, which has an average tuition of $15,000.

Originally introduced in the 1930s, cosmetology licenses were intended to control the quality of haircuts and protect consumers from health and safety risks. Since the 30s, however, the power of word of mouth and a bad Yelp review is likely more threatening to a barber than what a licensing board thinks of their barbering. The preservation of licensing is now an effort that protects the insiders (licensed barbers) from outsiders (talented, unlicensed barbers) and generates fees that members of state cosmetology licensing boards collect.

The arguments against occupational licensing I read, which were mostly from libertarian think tanks, were often contextualized with stories of immigrants with special cosmetological abilities that are not very prevalent in the US, who are unable to practice their craft without a license. So putting a stop to Big Haircut would not only help me in this very peculiar situation — it would also help immigrants. But it would also mean aligning with people who professionally identify as libertarians, who are often unserious people.2

I think of most libertarian ideas as pretty childish and obtuse but I struggle to rationalize why regulatory barriers such as occupational licensing should be so prevalent in the barbering industry. People should be able to cut hair without a license and paying $16 for a five-minute trim is kind of unreasonable. Not only did it get me riled up enough to write a blog post about it — I’m riled up enough to donate the risk premiums I generate from skipping haircuts to libertarian organizations lobbying against cosmetology licensing.

This claim is highly disputable.

Several times I’ve been tempted to write an anti-Libertarian manifesto, but not today.

Fun but thoughtful read!

Truly inspiring!